C++ Core Guidelines: Rules for Constants and Immutability

Making objects or methods const has two benefits. First, the compiler will complain when you break the contract. Second, you tell the user of the interface that the function will not modify the arguments.

The C++ Core Guidelines have five rules to const, immutability, and constexpr. Here are they:

- Con.1: By default, make objects immutable

- Con.2: By default, make member functions

const - Con.3: By default, pass pointers and references to

consts - Con.4: Use

constto define objects with values that do not change after construction - Con.5: Use

constexprfor values that can be computed at compile time

Before I dive into the rules, I have to mention one expression. When someone writes about const and immutability, you often hear the term const correctness. According to the C++ FAQ, it means:

- What is const correctness? It means using the keyword const to prevent const objects from getting mutated.

Now, we know it. This post is about const correctness.

Con.1: By default, make objects immutable

Okay, this rule is relatively easy. You can make a value of a built-in data type or an instance of a user-defined data type const. The effect is the same. If you want to change it, you will get what you deserve: a compiler error.

struct Immutable{ int val{12}; }; int main(){ const int val{12}; val = 13; // assignment of read-only variable 'val' const Immutable immu; immu.val = 13; // assignment of member 'Immutable::val' in read-only object }

The error messages from the GCC are compelling.

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Do you want to stay informed: Subscribe.

Con.2: By default, make member functions const

Declaring member functions as const has two benefits. An immutable object can only invoke const methods, and const methods cannot modify the underlying object. Once more. Here is a short example that includes the error messages from GCC:

struct Immutable{ int val{12}; void canNotModify() const { val = 13; // assignment of member 'Immutable::val' in read-only object } void modifyVal() { val = 13; } }; int main(){ const Immutable immu; immu.modifyVal(); // passing 'const Immutable' as 'this' argument discards qualifiers }

This was not the whole truth. Sometimes, you distinguish between the logical and the physical constness of an object. Sounds strange. Right?

- Physical constness: Your object is declared

constand can, therefore, not be changed. - Logical constness: Your object is declared

constbut could be changed.

Physical constness is relatively easy to get, but logical constness is. Let me modify the previous example a bit. Assume I want to change the attribute val in a const method.

// mutable.cpp #include <iostream> struct Immutable{ mutable int val{12}; // (1) void canNotModify() const { val = 13; } }; int main(){ std::cout << std::endl; const Immutable immu; std::cout << "val: " << immu.val << std::endl; immu.canNotModify(); // (2) std::cout << "val: " << immu.val << std::endl; std::cout << std::endl; }

The specifier mutable (1) made the magic possible. The const object can, therefore, invoke const method (2), which modifies val.

Here is an excellent use-case for mutable. Imagine your class has a read operation which should be const. Because you use the objects of the class concurrently, you have to protect the read method with a mutex. So the class gets a mutex, and you lock the mutex in the read operation. Now, you have a problem. Your read method cannot be const because of the locking of the mutex. The solution is to declare the mutex as mutable.

Here is a sketch of the use case. Without mutable, this code would not work

struct Immutable{ mutable std::mutex m; int read() const { std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lck(m); // critical section ... } };

Con.3: By default, pass pointers and references to consts

Okay, this rule is quite apparent. If you pass pointers or references to consts to a function, the intention of the function is obvious. The pointed or referenced object would not be modified.

void getCString(const char* cStr); void getCppString(const std::string& cppStr);

Are both declarations equivalent? Not one hundred per cent. In the case of the function, the pointer could be null pointer. This means you have to check in the function vai if (cStr) ....

But there is more. The pointer and the pointee could be const.

Here are the variations:

const char* cStr:cStrpoints to acharthat isconst;the pointee cannot be modifiedchar* const cStr:cStris aconstpointer; the pointer cannot be modifiedconst char* const cStr:cStris a const pointer to acharthat isconst; neither the pointer nor the pointee could be modified

Too complicated? Read the expressions from right to left. Still too complicated? Use a reference to const.

I want to present the next two rules from the concurrency perspective. Let me do it together.

Con.4: Use const to define objects with values that do not change after construction and Con.5: Use constexpr for values that can be computed at compile time

If you want to share a variable immutable between threads and this variable is declared as const, you are done. You can use immutable without synchronization, and you get the most performance out of your machine. The reason is quite simple. You should have a mutable, shared state to get a data race.

Data Race: At least two threads access a shared variable at the same time. At least one thread tries to modify it.

There is only one problem to solve. You have to initialize the shared variable in a thread-safe way. I have at least four ideas in my mind.

- Initialize the shared variable before you start a thread.

- Use the function

std::call_oncein combination with the flagstd::once_flag. - Use a

staticvariable with block scope. - Use a

constexprvariable.

Many people oversee variant 1, which is relatively easy to do right. You can read more about the thread-safe initialization of a variable in my previous post: Thread-safe Initialization of Data.

Rule Con.5 is about variant 4. When you declare a variable as constexpr constexpr double totallyConst = 5.5;, totallyConst is initialized at compile-time and, therefore, thread-safe.

That was not all about constexpr. The C++ core guidelines forgot to mention a critical aspect of constexpr concurrent environments. constexpr functions are pure. Let’s have a look at the constexpr gcd .

constexpr int gcd(int a, int b){ while (b != 0){ auto t= b; b= a % b; a= t; } return a; }

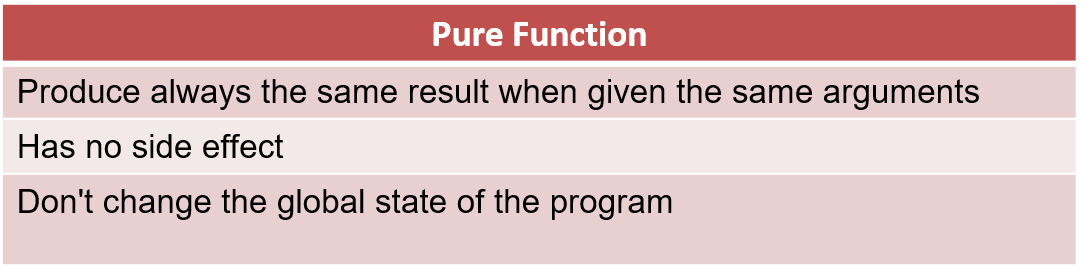

First, what does pure mean? And second, what does sort of pure mean?

A constexpr function can be executed at compile time. There is no state at compile time. When you use this constexpr function at runtime, the function is not, per see, pure. Pure functions are functions that always return the same result when given the same arguments. Pure functions are like infinitely large tables from which you get your value. Referential transparency is the guarantee that an expression always returns the same result when given the same arguments.

Pure functions have a lot of advantages:

- The result can replace the function call.

- The execution of pure functions can automatically be distributed to other threads.

- A function call can be reordered.

- They can easily be refactored or tested in isolation.

In particular, point 2 makes pure functions so precious in concurrent environments. The table shows the critical points of pure functions.

I want to stress one point. constexpr functions are not per se pure. They are pure when executed at compile time.

What’s next

That was it. I’m done with constness and immutability in the C++ core guidelines. In the next post, I will start to write about the future of C++: templates and generic programming.

Thanks a lot to my Patreon Supporters: Matt Braun, Roman Postanciuc, Tobias Zindl, G Prvulovic, Reinhold Dröge, Abernitzke, Frank Grimm, Sakib, Broeserl, António Pina, Sergey Agafyin, Андрей Бурмистров, Jake, GS, Lawton Shoemake, Jozo Leko, John Breland, Venkat Nandam, Jose Francisco, Douglas Tinkham, Kuchlong Kuchlong, Robert Blanch, Truels Wissneth, Mario Luoni, Friedrich Huber, lennonli, Pramod Tikare Muralidhara, Peter Ware, Daniel Hufschläger, Alessandro Pezzato, Bob Perry, Satish Vangipuram, Andi Ireland, Richard Ohnemus, Michael Dunsky, Leo Goodstadt, John Wiederhirn, Yacob Cohen-Arazi, Florian Tischler, Robin Furness, Michael Young, Holger Detering, Bernd Mühlhaus, Stephen Kelley, Kyle Dean, Tusar Palauri, Juan Dent, George Liao, Daniel Ceperley, Jon T Hess, Stephen Totten, Wolfgang Fütterer, Matthias Grün, Ben Atakora, Ann Shatoff, Rob North, Bhavith C Achar, Marco Parri Empoli, Philipp Lenk, Charles-Jianye Chen, Keith Jeffery, Matt Godbolt, Honey Sukesan, bruce_lee_wayne, Silviu Ardelean, schnapper79, Seeker, and Sundareswaran Senthilvel.

Thanks, in particular, to Jon Hess, Lakshman, Christian Wittenhorst, Sherhy Pyton, Dendi Suhubdy, Sudhakar Belagurusamy, Richard Sargeant, Rusty Fleming, John Nebel, Mipko, Alicja Kaminska, Slavko Radman, and David Poole.

| My special thanks to Embarcadero |  |

| My special thanks to PVS-Studio |  |

| My special thanks to Tipi.build |  |

| My special thanks to Take Up Code |  |

| My special thanks to SHAVEDYAKS |  |

Modernes C++ GmbH

Modernes C++ Mentoring (English)

Rainer Grimm

Yalovastraße 20

72108 Rottenburg

Mail: schulung@ModernesCpp.de

Mentoring: www.ModernesCpp.org

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!